Error of Margin

Alternative measures of corporate profits are sending mixed signals on the impact of tariffs on growth and inflation — it will take a few more months for clarity to emerge

Main Street and Wall Street have vastly different messages on corporate profitability these days. That’s a pity, because earnings are key to assessing the combined demand-and-supply impact of tariff policies and provide some insight into their eventual inflationary implications.

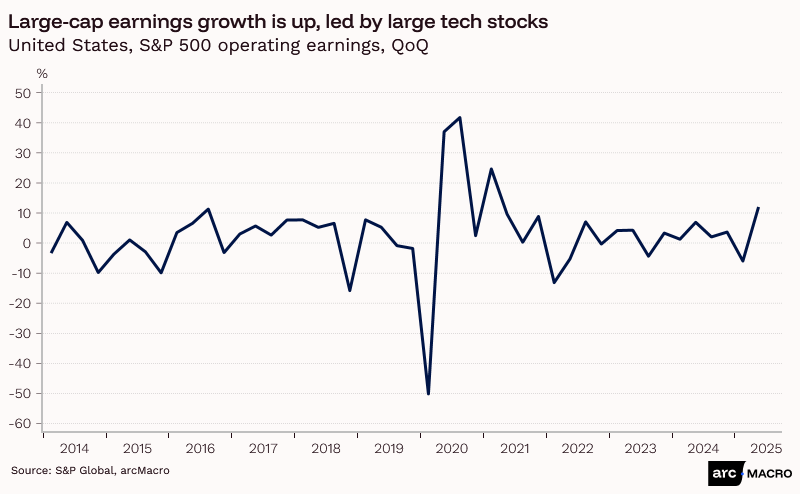

Wall Street is heralding strong earnings. Indeed, the first line of defence against those warning that the market is overvalued is to point to S&P 500 operating earnings growth of 12% YoY in Q2 (with Q3 earnings suggesting momentum will carry into the second half of the year). Tariffs? What tariffs?

Main Street is far more pessimistic. It's hard to find a middle-market CEO who isn’t worried about higher tariffs eating into their profits, and spending a large share of their time adjusting operations or pricing strategies to offset the impact.

They’re both right. They’re just looking at different data.

It’s true that earnings on the major stock indices are strong. But this is a poor sample of the US economy. That 12% earnings growth rate on the S&P 500 is heavily inflated by highly profitable large tech firms, and captures only the largest firms with the strongest pricing power.

These firms may be unaffected by tariffs or adapting well for the most part, but we can’t assume the same of smaller firms.

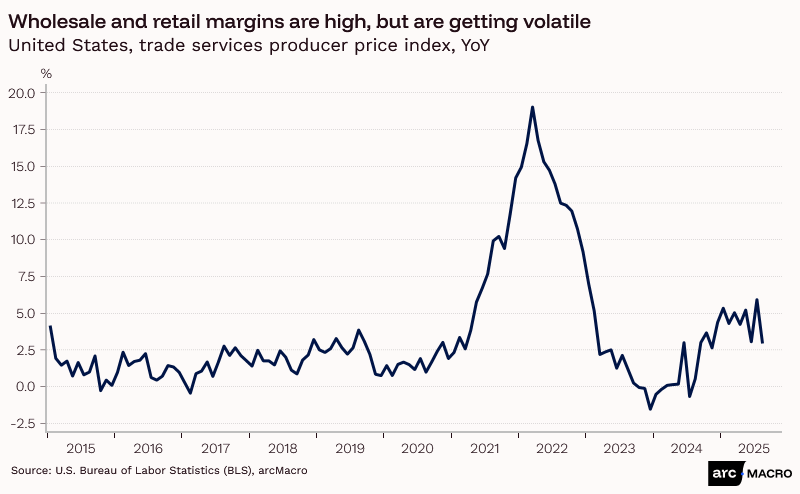

Let’s broaden the net a little. The producer price index measures inflation in the wholesale and retail sectors by comparing the purchase and sale prices of merchandise. This gives a crude sense of their ability to pass on costs.

Since 2023, the trade services PPI has grown at around 5% YoY, well above its historical average. It’s still high, but it’s starting to show some signs of falling.

We’ll get more PPI data when the BLS catches up on its backlog of data releases, but for now, this is an inconclusive signal.

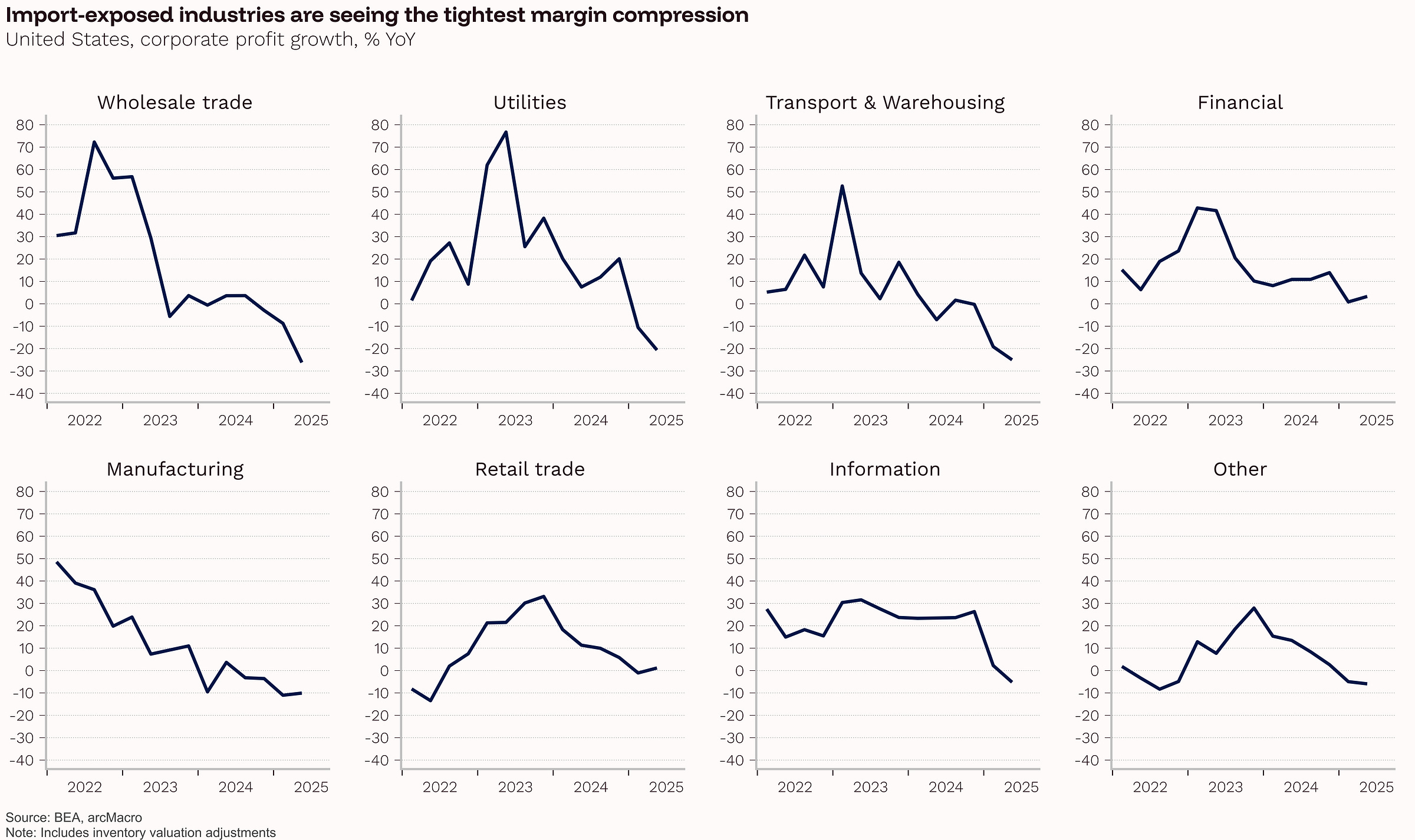

We can get an even wider “full economy” perspective by looking at the BEA’s measurement of corporate profits by industry.

This shows a clear drop-off for import-sensitive industries (wholesale trade, transport & warehousing) at the beginning of 2025 that can be attributed to tariff policy. This tells us that there is a degree of cost absorbtion happening, which will be helping to dampen the immediate inflation hit.

But we know there are some complicating factors here, too. The BEA’s treatment of depreciation and inventory costs, as well as a normalization after a period of very high capital gains, has distorted the clarity of the signal somewhat.

So, what do we make of all of this? Here is my take:

We don’t yet have a clear idea of how inflationary tariffs will prove, as we can’t assess how much their demand-dampening effect will offset their direct cost impact cleanly.

Tariffs arrived at a time of strong margin growth, so there is space for firms to absorb as a share of the hit; mitigation policies are being put into place, which are costly over a longer period but limit the immediate hit.

Inventory stockpiles built before tariffs were enacted are delaying the pass-through, further obscuring the final effect on inflation.

We know that uncertainty is reducing capex in some sectors—this is helping cost management and improving margins in the short run.

Pass-through will vary greatly by sub-industry and even firm-to-firm in the same industry.

Taking this all together, we won’t see full pass-through until well into 2026. Until then, we should be taking anecdotal evidence and resources such as the Beige Book very seriously.